- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Literature»

- American Literature

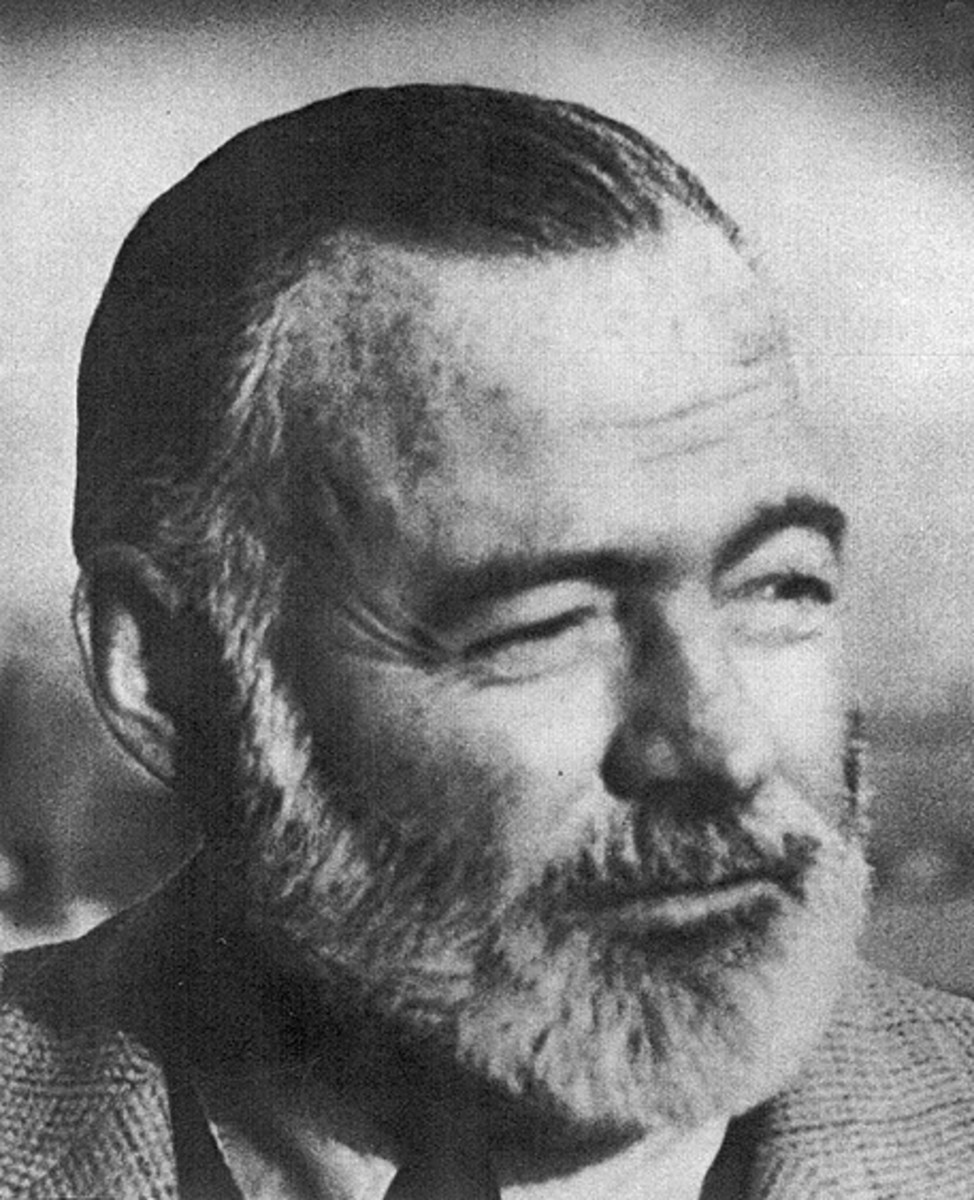

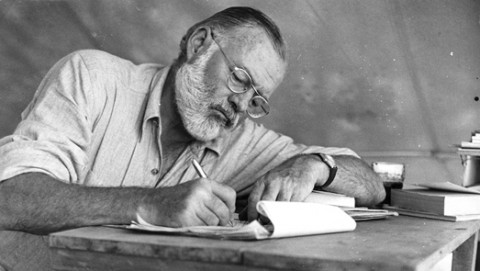

Ernest Hemingway - An Undefeated Man

Defined from Youth

At the tender age of two, Ernest Hemingway exclaimed to his mother he was, in fact, “Fraid o’ nuthin!” Indeed, the man, perhaps in an effort to prove his fearlessness, could not turn down a challenge: war, bullfighting, boxing, big-game hunting, and deep-sea fishing. Hemingway, a passionate sportsman, world traveler, and romanticist, gladly promoted a larger-than-life, mystical persona. Undoubtedly, one of the greatest (and most criticized) writers of the twentieth century, it is difficult to distinguish him from the characters in his novels.

Hemingway was born and raised in Illinois by strict parents in an upper-middle-class neighborhood. His mother, Grace, fiercely ambitious, dreamed of becoming an opera star in her youth. His deeply-religious father, commonly known as Ed, was a physician who met his wife, Grace, in high school (Baker 2). With only a one year age difference between them, Ed and Grace would have six children; the last would arrive when Grace was 43 years old.

Hemingway was the second child of the couple, less than two years younger than his sister Marcelline. His mother, a bit eccentric, raised them as twins. She even held her daughter back from starting school so they could be in the same class. Grace, conducting her own experiment in androgyny on her children, would dress them in “fancy frocks and floppy little-girl hats” and on other occasions would dress them in boys’ overalls. The children each had china tea sets and air rifles. It was terribly confusing for the three-year old Ernest, who was terrified that Santa Claus might not know he was a boy when the time came to deliver presents (Harmon). Hemingway’s participation in all types of sports, travels, love affairs, quarrels, and fist-fights served as an avenue to assert his overwhelming need to prove his masculinity and as the backdrop to his famous literary works and heroes.

Hemingway had wonderful outdoor excursions with his father and learned how to hunt, fish, and be resourceful in the woods. He turned his youthful excursions into a collection of stories in which the hero, Nick Adams, inherited the adventurous spirit of the young Ernest (Baker 147). When he was twelve-years old, his father slipped into progressive depressions and, eventually, committed suicide in 1928 when his health was deteriorating. Hemingway would blame his mother for his father’s suicide, which left him with serious emotional scars. He would translate the experience into the story The Doctor and the Doctor’s Wife (Encyclopedia of World Biography).

The work is a reflection of Hemingway's life.

Even at a young age, Hemingway was gifted with an active imagination, which was reflected in his writing. He had realized his passion for writing during his teens. His poems, stories, and weekly column for his high school newspaper included stories about mayhem and suicide. Around this same time, Hemingway discovered an enthusiasm for boxing. Using the music room for a ring, he would “box” a succession of his classmates. Grace had reached her limit and banished them from the house but they simply moved their fights to a small gymnasium or outdoors. He would make a few Saturday morning visits to Forbes and Ferretti’s or Kid Howard’s to learn boxing techniques and to keep his eyes and ears open for the stories people would tell. The Tabula printed one of his earliest short stories, “A Matter of Colour.” It was a witty tale told from the perspective of an old boxing manager to a youthful listener. Hemingway would continue to seek out exciting arenas of life to feed his creativity (Baker 22).

Ed wanted Ernest to follow in his footsteps and become a doctor. Always a rebel, Hemingway refused even to attend college; rather, he became a reporter on the Kansas City Star. He credits the newspaper editor with providing him “the best rules I ever learned for the business of writing. The style sheet he received on his first day read: “Use short sentences. Use short first paragraphs. Use vigorous English. Be positive, not negative” (Harmon).

The year 1918 marked the beginning of World War I. Ernest wanted to serve in the military but was rejected because of poor eyesight. Undeterred, he volunteered as a Red Cross ambulance driver in Italy. He was badly wounded while saving a soldier’s life (St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture). During his five-month recuperation at a hospital, he became infatuated with his nurse, Agnes Von Kurowsky. She allowed the “love affair” to progress only to the “kissing stage”’ and Hemingway was left yearning for more. He turned Agnes into the heroine Catherine Barkley in the novel Farewell to Arms (Harmon).

Hemingway’s passion for travel was sparked. He traveled throughout Europe and often wrote of his experiences. It was almost viewed as a duty; and he insisted, “Every artist owes it to the place he knows best to either destroy it or perpetuate it.” He was always “on the move searching for the next place, subject destination, wife, or physical challenge” (Tall).

Hemingway married Elizabeth Hadley in 1921. He was known for falling in love quickly and deeply and falling out of love in the same manner. It was during his marriage to Elizabeth he met Lady Duff Twysden, a chic, alcoholic Englishwoman. Immediately impressed, he succumbed to her flirtations but she did not follow through with an affair. Like Agnes, she was transformed in Lady Brett Ashley in the novel The Sun Also Rises. The marriage to Elizabeth did not last long. He engaged in an affair with her friend, Pauline Pfeiffer; and after their divorce, he married Pauline in 1927. He describes the triangle in the novel A Movable Feast, which was published posthumously. He wrote, “We had already been infiltrated by another rich (Pauline) using the oldest trick there is. It is that an unmarried young woman becomes the temporary best friend of another young woman who is married, goes to live with the husband and wife and then unknowingly, innocently, and unrelentingly sets out to marry the husband…one is new and strange; and, if he has bad luck, he gets to love them both” Desnoyers).

Hemingway saw his first bullfight in 1923 and was so enraptured with the sport he began an “exhaustive study” of it. He was the kind of man who, when a subject interested him, he sought out to find out everything he could on it. Published in 1932, Death in the Afternoon is still one of the most comprehensive studies of the sport (Desnoyers).

Pauline’s Uncle Gus gave the couple an extraordinary gift in 1932: a ten-week African safari. They hunted eland, antelope, gazelle, leopards, and of course, lions. Nairobi fascinated Hemingway; and the trip served as a fantastic inspiration for some of his finest work: Green Hills of Africa, The Snows of Kilimanjaro, and The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber (Baker 250).

Hemingway was a war correspondent during the Spanish Civil War (1936) and from those experiences he wrote the novel For Whom the Bell Tolls. He had followed Spanish politics closely believing in their working class rituals without embracing socialism; and he used it as the setting for his love story (Reynolds 22).

He was known to have severe mood swings, sometimes for long periods of time; at other times, they might last only hours. It is difficult to distinguish whether his depressions were precipitated by writer’s block or whether the reverse is true. This is often the case with manic-depressives. The depressions would occur more frequently as he aged. Hemingway referred to these periods as “Black-Ass symptoms” (Hotchner 72).

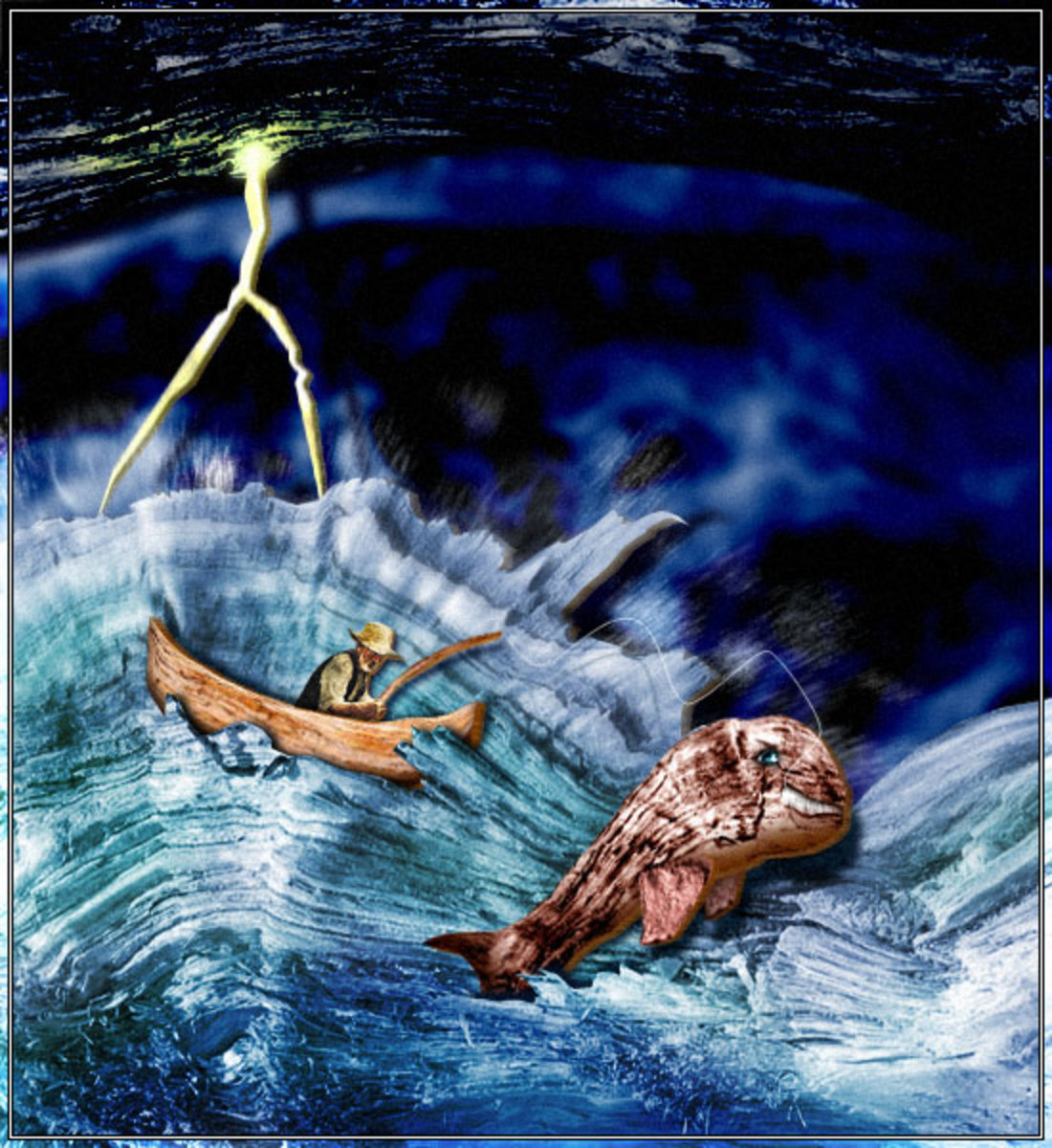

He was living in Cuba when a friend came to visit him. Late one evening, Hemingway came to his friend’s room “tentative, almost ill at ease” with a manuscript in his hand saying, “Wanted you to read something. Might be an antidote to Black-Ass.” It was entitled The Old Man and the Sea. It was a theme that always intrigued Hemingway, “Man can be destroyed, but not defeated.” A battle between a tired old Cuban fisherman and a giant marlin, it was his greatest novel since the 1920s; and it would earn him the coveted Pulitzer Prize in 1953 and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954 (Encyclopedia of Word Biography).

Visit the author's home

- The Ernest Hemingway Home & Museum

Located at 907 Whitehead Street in Old Town Key West, Florida, Ernest Hemingway lived and wrote here for more than ten years.

The Later Years

Depression, anxiety, and insomnia plagued Hemingway, since 1919. When he was euphoric, nothing could discourage him but when his moods crashed, he would become “paranoid, moody, and implacable” (Reynolds 235). Mary, his fourth wife, seemed to be the only one of his wives who could tolerate his bizarre behavior. She could see both sides of her husband who could be even more charming, apologetic, and devoted after a harrowing argument.

His health had been failing him for some time, most notably, during his last ten years: high cholesterol, liver problems, an enlarged aorta, erratic blood pressure, and eczema. In 1957, doctors ordered him to quit drinking alcohol and prescribed medications like Serpasil, Doriden, and Ritalin in an attempt to help with his anxiety, depression, impulsivity, and hyperactivity (Reynolds 236). His physical condition was almost identical to that of his father. With each passing depressive episode, it was increasingly difficult for Hemingway to “climb back out” (Reynolds 321). His letters would include reference to suicidal thoughts including detailed directions on how he would carry it out (Reynolds 335). By 1960, his paranoia reached a climax, “’they’re trying to catch us…the F.B.I.,” he said (Reynolds 338). He was hospitalized and was treated with electroshock therapy. After a brief recovery, he slipped again into depression and paranoia. Unable to write, unwilling to go to a psychiatric hospital, and unable to endure life anymore, Hemingway went into his basement early one morning and shot himself in the head.

He lived an incredible life and gave our culture the All-American story: young men who follow their dreams, transform themselves, who succeed beyond their wildest dreams; and yet, in many cases, they do not survive. His life and works are forever intertwined.

His friend, A.E. Hotchner, says it best in the biography Papa Hemingway: Ernest had it right: “Man is not made for defeat. Man can be destroyed but not defeated.” He destroyed himself physically but was not defeated because he continues to live on through the legacy of his superb writings.

A 1977 biographical video includes historical footage of Hemingway

List of Hemingway's Works (alphabetical)

A Matter of Colour

Across the River and Into the Trees

Death in the Afternoon

Farewell to Arms

For Whom the Bell Tolls

In Our Time

Men Without Women

Snows of Kilimanjaro

The Doctor and the Doctor’s Wife

The Green Hills of Africa

The Old Man and the Sea

The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber

The Sun Also Rises

To Have and Have Not

Torrents of Spring

Posthumously published (by year):

A Movable Feast (1964)

The Fifth Column and Four Stories of the Spanish Civil War (1969)

Islands in the Stream (1970)

The Nick Adams Stories (1972)

The Dangerous Summer (1985)

The Garden of Eden (1986)

Works Cited

Baker, Carlos. Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story. New York: Macmillan, 1968.

Desnoyers, Megan. “Ernest Hemingway: A Storyteller’s Legacy.” Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives. Winter 1992. 2 May 2003.

“Ernest Hemingway,” St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. 5 Vols. St. James Press, 2000.

“Ernest Miller Hemingway.” Encyclopedia of World Biography 2d Ed. 17 Vols. Gale Research, 1998

Harmon, Melissa. Ernest Hemingway: The Man and His Demons.” Biography Magazine. May 1998.

SIRS Knowledge Source, 2003.

Hotchner, A.E. Papa Hemingway. New York: Random House, 1968.

Reynolds, Michael. Hemingway: The Final Years. New York: W.W. Norton, 1999.

Tall, Deborah. “ There Where of Writing: Hemingway’s Sense of Place.” The Southern Review. Spring 1999. SIRS Knowledge Source, 2003.

By Liza Lugo, J.D.

© 2012, Revised 2014. All Rights Reserved.

Ms. Lugo retains exclusive copyright and publishing rights to all of her articles and photos by her located on Hub Pages. Portions of articles or entire content of any of these articles may not be used without the author's express written consent. Persons plagiarizing or using content without authorization may be subject to legal action.

Permission requests may be submitted to liza@lizalugojd.com.

Originally written and published January 3, 2012. Latest corrections and edits made on February 23, 2015.