Fourth Amendment: Understanding Rights against Unreasonable Search and Seizure

Disclaimer: This article is for general informational purposes only and is not to be used or interpreted as legal advice. If you have a legal issue, seek out the services of a licensed attorney.

Personally, think it is imperative for everyone to understand what their rights are under the law, which is not limited to the statutes and plain language of the Constitution but also those laws made by the judiciary in their interpretation of the law, which is known as case law.

The Facts in Terry v. Ohio

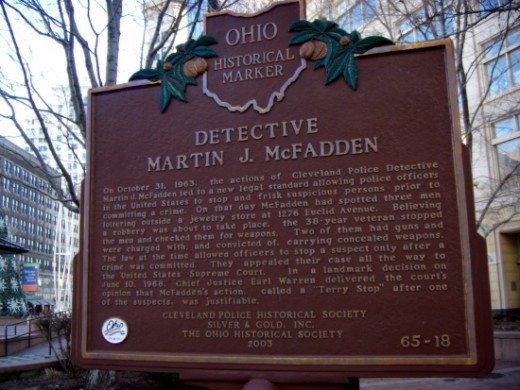

An experienced police detective, Martin J. McFadden, observed two men on a street corner in Cleveland around 2:30 p.m. The detective believed the men were “casing” the store for a robbery attempt. The men had been walking up and down in front of the building, looking in the window and returning to the corner to talk.

A few minutes later, a third man joined them; then he left. The detective approached them and identified himself. He then asked the men for identification. The men mumbled responses, so the detective frisked them and found handguns. They were arrested for carrying concealed weapons and were, consequently, were convicted.

The Supreme Court of the United States granted certiorari, meaning the Court was willing to hear the case (Hickey, 2001, p. 148).

The Issue in Terry v. Ohio

The issue in this case was whether it is always unreasonable for police to seize a person and subject him to a limited search for weapons unless there is probable cause for an arrest. The Supreme Court of the United States held the stop and frisk practice did not require probable cause but reasonable suspicion of criminal activity is taking place. The frisk must be “confined in scope to discover weapons for the assault of the police (Hickey, 2001, p. 149). The justification of this decision lies in the necessity to protect police officers and the public.

The Court refused to develop a bright-line rule to determine when the encounter becomes an arrest. There are differences in stops and arrests. A stop is a temporary detention; an arrest is a “more intrusive and lengthy interference with a suspect’s liberty” (Hickey, 2001, p. 149). A stop is based on reasonable suspicion; an arrest is based on probable cause. The search incident to an arrest is to produce evidence of criminal activity. A frisk of outer clothing is solely for finding weapons.

The original holding in Terry v. Ohio has been expanded to permit investigations into crimes. While in the Terry case reasonable suspicion could be established through the personal observations of police officers, it was expanded upon in Adams v. Williams where suspicion could be established by using an informant’s tip. Similarly, in Alabama v. White, anonymous informant tips “may be supplemented with corroborative police investigation” (Hickey, 2001. P. 155). In U.S. v. Sokolow, the Court held drug courier profiles, which identify people who may be transporting illegal drugs was constitutional. These profiles are used at transportation centers like airports, train stations, or bus terminals. The profile is part of the information police use to determine reasonable suspicion and include: paying for tickets with large amounts of cash, traveling under a false name, traveling from a source city, staying at a destination for a short period of time, and nervous appearance (Hickey, 2001, p. 156).

What the Holding in Terry v. Ohio Means

The United States Supreme Court decision in Terry v. Ohio, is significant with regard to Fourth Amendment rights. There are several important issues within the case:

1. For Fourth Amendment purposes, the court determined a “stop” was a seizure and a “frisk” was a search;

2. For the first time police were allowed to conduct searches and seizures without probable cause. “Stop and Frisk” could be conducted based on reasonable suspicion, a less demanding standard of proof;

3. It is an effective accommodation between the competing interests of citizens’ privacy and protection of the police and the public. In order to balance those interests, the court used a test that balances suspects’ privacy interests with society’s need to conduct the challenged search.

If officers fail to investigate suspicious activity, their safety and the safety of the public could be jeopardized. In Terry v. Ohio, the Supreme Court of the United States held “stop and frisk” procedures were constitutional (not in violations of a citizen’s Fourth Amendment rights).

A “stop” is a temporary detention of someone for questioning by the police. This detention is a seizure under the Fourth Amendment. A “frisk” is a pat-ddown of the detained person’s outer clothing to determine if there are weapons present. In this case, the Court allowed police to stop, question, and frisk someone without probable cause if there was reasonable suspicion to believe they were involved in criminal activity (Hickey, 2001, p. 148).

The Ruling Terry v. Ohio

The ruling in Terry v. Ohio was designed to maintain the protective interests of police officers and the public, which outweigh the personal privacy interests of the individual. The stop and frisk is limited in scope and individuals can expect a significantly lesser expectation of privacy than in their own home, where the expectation is greatest.

Still, 56 years later, there is a lot of controversy surrounding the case; it has created exceptions to the warrant requirement in a search. It has also evolved into a plain-touch doctrine, as in Minnesota v. Dickerson. Police, if lawfully present in the place where the search is conducted without a warrant, may conduct a pat-down/frisk; and, if the item they feel is immediately recognized as contraband, it may be seized (Hickey, 2001, p. 157). While Terry was originally a search for weapons, it opened the door for Dickerson to evolve into a sort of frisk for evidence that is not a threat to police officers.

Dissenting Opinion in Terry v. Ohio

The Terry case left an opening for abuses like racial profiling to occur. There is no outlined description for what constitutes “reasonable suspicion” nor a guideline to distinguish when an encounter becomes an arrest. The officer’s attention was attracted by two men he had never seen before standing on the corner; and he was unable to say what first drew his eye to them. According to the officer, “they didn’t look right at me at the time.”

According to Justice Douglass’ dissenting opinion in Terry:

"I agree that petitioner was “seized” within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment. I also agree that frisking the petitioner an dhis companions for guns was a “search.” But it is a mystery how that “search” and that “seizure” can be constitutional by Fourth Amendment standards unless there was “probable cause” to believe that:

1. A crime had been committed, or

2. A crime was in the process of being committed ,or

3. A crime was about to be committed…If loitering were an issue…there would be “probable cause” shown. But the crime here is carrying concealed weapons, and there is no basis for concluding that the officer had “probable cause.

We hold today that police have greater authority to make a “seizure” and conduct a “search” than a judge has to authorize such action. We have said precisely the opposite over and over again.”

Douglass also recommended the possibility of an additional constitutional amendment by the people to alter the Fourth Amendment rather than have this decided by the Supreme Court. But, of course, that has not occurred.

Read the Court's opinion:

- Terry v. Ohio

FindLaw | Cases and Codes

Stop and Frisk in the 21st Century

Recently, the New York City Police Department found itself under fire for its controversial stop and frisk policy, known as "Clean Halls." Officers made trespass stops outside private residential buildings (with landlord permission). In 2011, Jaenean Ligon sent her 17-year old son to purchase ketchup. Two plainclothes officers stopped and frisked the teen outside the family's building. But Ligon's son was not the only person stopped by police officers. In fact, NYPD made 4.4 million stops between January 2004 and June 2012. Over 80% of these 4.4 million stops were of blacks or Hispanics, as was Ligon's son.

In 2013, Manhattan federal court judge, Shira Scheindlin, in the case of Floyd, et al v. City of New York, ordered police to stop making trespass stops. An important part of the reasoning was to "judge the constitutionality of police behavior, not its effectiveness as a law enforcement tool." In all, 19 cases were included in the case at hand. Judge Scheindlin found the NYPD's program unconstitutional.

Read Judge Scheindlin's opinion and order

- Floyd, et al v. City of New York

Provided by the New York Civil Liberties Union.

In my opinion, decisions like Terry and Dickerson simply show the support of the judiciary branch to the legislative “War on Crime” and the “War on Drugs” campaigns and reduce rights of privacy to individuals.

The Fourth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States provides:

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue but upon probable cause…” (not "reasonable suspicion").

I find there is a bit of contradiction with the Terry decision, particularly, in light of their prior decision the same year in Katz v. United States. Although Katz was a wiretapping case, the Court held “the Fourth Amendment protects people, not places.”

I agree with Justice Douglass that the decision can lead us closer to a totalitarian regime, where police, whenever they become reasonably suspicious of people on the street can stop, detain, and frisk them as they go about their business. Officers should not have the authority to do so unless there is "probable cause." To that aim, I see Terry v. Ohio as judicial activism given that "probable cause" is clearly necessitated by the Fourth Amendment. The people have a right to be secure in their persons as so defined.

WORKS CITED

Adams v. Williams, 497 U.S.143 (1972).

Alabama v. White, 496 U.S. 325 (1990).

Hickey, Thomas J. (2001). Criminal Procedure.

Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347 (1967).

Minnesota v. Dickerson, 508 U.S. 366 (1993).

Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968).

U.S. v. Sokolow, 490 U.S.1 (1989).

Wills, Kerry, et al. "NYPD's controversial 'Stop and Frisk' policy ruled unconstitutional." New York Daily News. January 8, 2013. http://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/nypd-controversial-stop-frisk-policy-ruled-unconstitutional-article-1.1235578. Access date: 12/13/14.

By Liza Lugo, J.D.

© 2012, Revised 2014. All Rights Reserved.

Ms. Lugo retains exclusive copyright and publishing rights to all of her articles and photos by her located on Hub Pages. Portions of articles or entire content of any of these articles may not be used without the author's express written consent. Persons plagiarizing or using content without authorization may be subject to legal action. The articles by Ms. Lugo regarding legal issues are purely academic in nature and do not constitute legal advice. For advice on legal matters, consult a licensed attorney in your jurisdiction.

Permission requests may be submitted to liza@lizalugojd.com.